Interview between Tom Godfrey and Robin Kerr (Founder of G-Force) conducted over email, March-April 2021.

Tom Godfrey. It'd be great if you could start by talking about when and why you started G-Force. Often things are initiated because of a frustration or lack of something else – what were you responding to or against?

Robin Kerr. Started it in my second year on BA fashion course at NTU as I enjoyed the making process so much, set up a small studio in my flat and soon discovered there was a demand. Initially I was making jackets from vintage chenille curtains to sell in a vintage store, Pennyfeathers and then people wanted custom made trousers and shirts. Soon outgrew the space in my flat and rented the top floor above Ben Bowers restaurant at the top of Derby road, no lift!! Opened the space on a Saturday and had regular buyers.

Found a space in town on Bottle lane and set up a larger studio with another student from NTU and we made stock to sell every Saturday under the name Jakeman and Kerr, there was an anonymous white door and we wanted it to look like a solicitor’s office from the outside. By which time we graduated this had become a full time occupation.

I sold part of my graduate collection to Paul Smith and started producing that along with hand knitted sweaters for his store. Launched the label G Force and opened the first shop in 1980 in Hockley with a small factory on Fletcher gate. I guess it was driven by not wanting to work in mass production and develop a brand of alternative clothing. We were probably one of the first streetwear brands

TG. When we spoke together recently, you mentioned there were different themes and narratives that informed your collections. Could you describe some of the different collections you made, and what prompted and drove these narratives that you were creating and exploring?

RK. From the earliest collections it was all about building a narrative to hang the concept on which would be easily recognised by the consumer, it was always about having fun and creating collections with energy.

There were many examples:

LAND ARMY where were worked with used grain sacks with great prints already on them, fake grass, felted knits, industrial felt and heavy denims.

PROTECT AND SURVIVE we built a narrative around the SAS survival book and Japanese earthquake survival guidance, using strong graphics and text around survival, hazard warning tape, labels and graphics with survival tips, bonded fabrics, silver foil survival sheets, padded jackets, reinforced panels, bullet proof jackets and luggage.

REPAIR AND WEAR Graphics and labels around recycling, the weather symbols, stitched repairs and worn denim, blanket stitch, old army blankets, canvas tarpaulins, industrial fabrics.

Each time we had a stand at Paris fashion week and dressed it to match the narrative

TG. There appears to a recurring and ongoing interest in the relinquishment of control – in regards to the designing & construction of garments as well as the the onward life of a G-F garment. This is demonstrated by the 'Design your own trousers' scheme in your stores, as well as labels inside your jeans that recommended boil washing, which over time would alter the appearance of that item. What was it about working like this and embracing these processes that was so important for you?

RK. As we were making the garments in our own factory, we had total control, the thinking was that the garments had to be over engineered and built rather than sewn together in the cheapest way. We felt that this was an important USP and I wanted to communicate this with humour hence the large labels with instructions of how to wash, dispose of and warnings of possible harassment or death. G Force clothes were designed to last. These were garments ‘beyond’ fashion. I know people who still wear clothes they bought in the 80’s. My kids now wear the clothes that I made and wore and they still look good.

Build your own trouser gave the consumer the ability to create within the parameters of the G Force concept.

TG. The branding and care labels inside your clothes are nearly as iconic as the clothing itself. They appear to assist G-F with becoming a brand that is established upon a manifesto, not just an aesthetic. The labels are quasi-contractual, emboldening the wearer whilst negating responsibility for them! Can you talk more about your use of labels and how they bolstered the identity of G-F as a whole?

RK. The labelling was about giving the information to the consumer that we were legally bound to but giving them much more, they told a story but were also humorous and often tongue-in-cheek. The labelling became more important for each collection and was a way of putting the narrative inside the garment or often they would appear on the outside using the same white cotton with black stencil or simple graphics.

The main handle of the narrative was once you bought the clothes then we no longer could be held responsible to what might happen if you wore them. I think that dates back to being a student on a Friday night wearing things made often that day, running the gauntlet through Market Square to the Playhouse bar.

TG. You spoke recently about the joy of seeing 2nd & 3rd generations now wearing and reappropriating G-F. How does it feel seeing G-F being worn by younger generations?

RK. Because the garments were over engineered, they have an extremely long life, often the sizing was over-sized partly to allow movement using engineered cutting and I like working with scale meaning that they still look good today. It great to see younger kids wearing it in their way mixing it with current brands or other vintage pieces.

I have seen pieces on the metro in Paris, Pompidou Centre, beaches in the south of France, Tokyo underground and regularly in Nottingham.

TG. What were some of the production techniques that you were experimenting with at that time? I understand that you would incorporate non-traditional materials into the clothes you were making, could you talk about some of these? Be as technical as you need.

RK. I was keen to find new materials, I would go to all the fabric fairs in Paris, Milan and Florence so pick up on trends then come back and find a way of getting a stronger result using dead stock fabrics, industrial fabrics and materials not designed for garments.

Working with Kevlar to develop ultimate protection in the form of bullet proof panels, stab prof nylons to work into jackets often bought by bouncers. Rubber flooring and heavy latex to add layers of protection.

We even developed fabrics impregnated with seeds that grew to form the text for an invite to a Paris show. I would over print them, dye, quilt, felt, stonewash, bond, coat, and laminate them.

I would investigate construction and rent machines not normally used for garment making to over engineer construction, heavy industrial threads, gluing and bonding or laminating instead of sewing. Industrial zips and fastenings.

TG. Motifs, pictograms and text would be rendered through knit, as opposed to being printed or embroidered. What was it about the imagery becoming a core part of the integrity of that garment that was so important to you? Again it seems to connect to this idea that the clothes were 'saturated' with a narrative and intention, as opposed to this being superficially 'applied' to the garment.

RK. The graphics around the narrative was so important and that was communicated through print in both labels and fabric print, embroidery. Initially I tried using imagery in jacquard knit mainly through hand knit and this became so big that sales outstripped production so I worked with domestic knitting machines on power units to produce a double bed jacquard which is quite heavy and when washed and felted became a solid fabric that fitted well the concept of over engineering.

The first garments produced by this method proved to be very expensive so I added more detail through construction using a blanket stich machine and the most expensive zip you can buy (made for the US airforce). Retailing at £120 which at the time was high but they sold worldwide.

This was the ultimate textile with the graphics being embedded into the fabric rather than a print on the surface.

TG. Through the archive materials you've shown me recently (adverts, invitations, shop interiors) it's clear that the G-Force 'brand' was totalising, that everything associated with what you were doing was vital and considered essential to the integrity of what you were doing. The attitude of establishing a philosophy, that permeates everything, feels extremely progressive as a mindset, particularly at that time perhaps. Can you talk about how you managed to do this? and perhaps the collaborations you formed that could both upheld but expanded your ambitions?

RK. Early on it was about creating a complete look, initially attached to music trends, from early punk, new romantics, rockabilly, Latin/disco zoot suits, to dance bands with loose fitting oversized workwear.

Often these bands would buy the clothes from our store in London or when we sold to Johnsons on the Kings Road London.

Being able to produce everything in the factory it was possible to make anything, so the range could be quite experimental. We had the ability to try things out, without a huge cost implication, so we could just make one thing and test the market and adapt. The only thing we could not make were shoes. We teamed up with factories in Northampton who had capacity as traditional goodyear welted shoes were not in demand as the high street was flooded with cheap cemented shoes. We could produce over engineered footwear that was designed to last, the bulk with DM soles or commando soles. In the mid to late 80’s we would sell over 200 pairs of shoes a week from the small shop in Hockley.

TG. The shop designs are very memorable, and appear to have made G-F a destination as well as an application. Can you talk about the shops, and the thinking that went into this? As I understand, Hockley in Nottingham where you had your first shop wasn't the destination it is now. Be great to hear about the localities you inhabited back then, both in Nottingham, Paris and Tokyo?

RK. I chose Hockley because it was cheap, on the edge of the Lace Market and close to the centre. In the early 80’s it was a busy (but not trendy) area with shops servicing the factory workers in the Lace Market: butchers, fruit shop, dry goods store, a proper haberdashery shop, old school shoe shop, 70’s fashion stores like Jeffs, Continental House, army surplus, greasy café and traditional pubs. Next door to us we had the surgical appliance store, which somehow seemed kind of fitting. There was no passing trade for our market so all word of mouth, gradually the area picked up but was never as busy as the developers predicted.

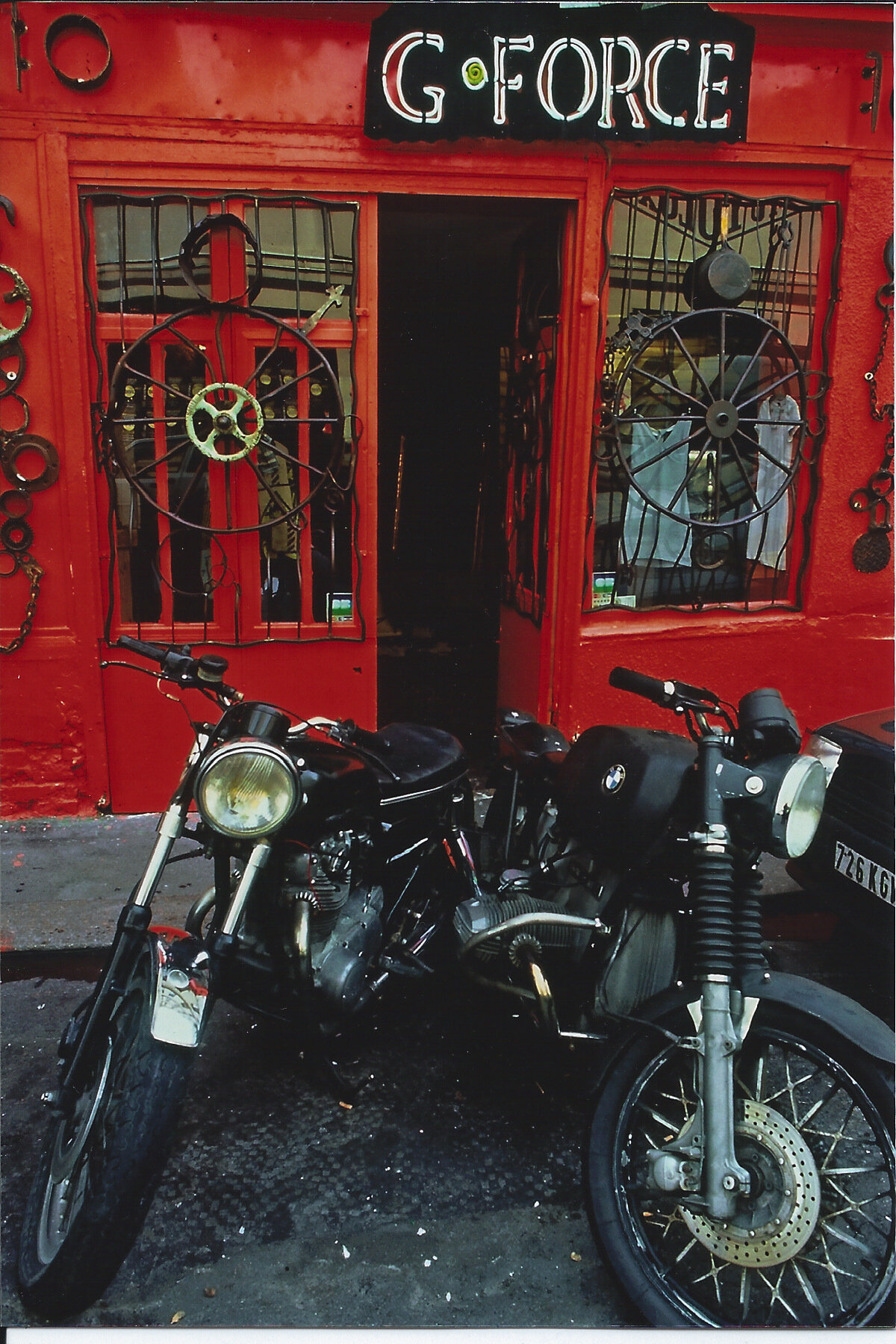

The interior and exterior were important to communicate the philosophy of the brand, in the beginning it was all painted grey including the windows so you could not see in apart from the small glass door this was to create an illusion of exclusivity and to rebel against the endless window dressing. The window was used to display the shoes on the inside therefore using space efficiently.

The shop windows were finally opened up in 1985 when John Eager refitted the shop in the industrial recycled style, he went on to fit our shop in Paris and Brussels followed by shops for Freelance a French brand that I also worked for.

In Tokyo we initially sold to small stores in the Harajuku area then we signed a distribution deal and they distributed to all the key independent stores across Japan. They would display the garments in a similar environment to our stores, lots of rusty metal and raw wood.

TG. Your clothes were worn by many individuals in the public eye, Cher being one example who graced the front of the Sunday Times Magazine one weekend in the early 1990's. Another example being the memorable moment Eric Cantona left his house wearing a G-F cardigan to a barrage of paparazzi the morning after his infamous 'flying kick' incident. By wearing your clothes, it appears certain individuals embraced a level of protection afforded to them by the ethos of the brand, as well as the confrontational use of apocalyptic pictograms and exuberant unconventional design. Do you think there was a sense of certain individuals seeking protection and deflection through G-Force clothes?

RK. In Nottingham we tended to attract a cult following from those who were in on the alternative night scene. It was all about being seen at night in the right bar or club in our clothes. I mean if you were trying to get into The Palais in G Force, well forget it, but The Asylum definitely.

This spilled out into the other cities and countries we sold to, you would see garments in all the hip bars in London, Tokyo, Paris or Brussels and celebrities soon became aware of the brand.

I think they were attracted to the brand as it was a small and independent producing heavy duty over engineered garments that gave one a sense of protection and long lasting identity without being too much of a ‘fashion brand’ and we never ‘gifted’ our garments, they were always bought. I think they also felt like they had discovered us, which gave them a feeling of exclusivity, that we certainly didn’t aspire to.

G Force clothes found their way into the 90’s cult French film Chacun Cherche Son Chat directed by Cedric Klapisch who was a regular customer and follower of the store in Paris.

G-Force Garments (RK Archive)

Further G-Force garments

G-Force Adverts.

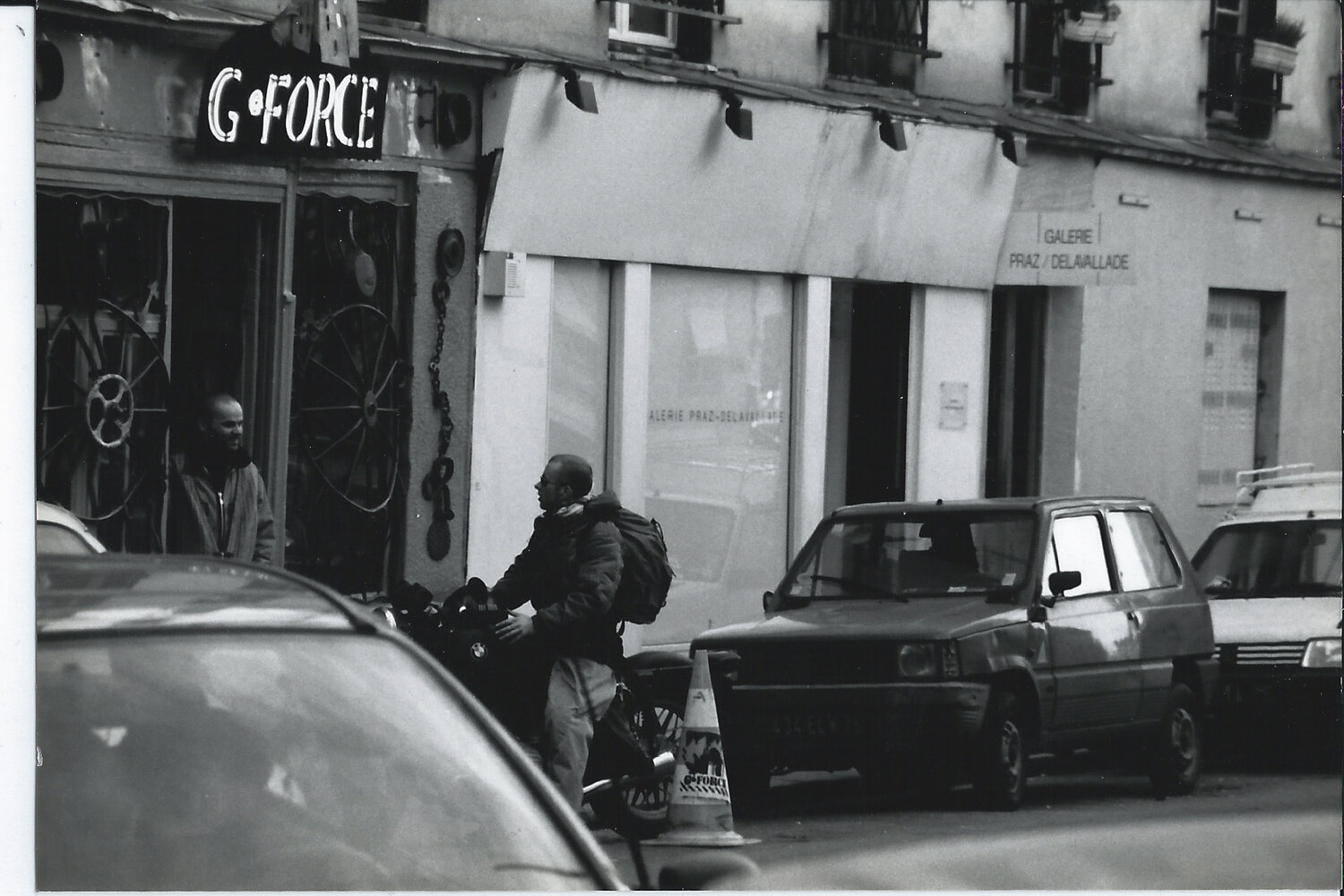

G-Force shops